The early 20th century was a formational period for Wooster and Wayne County. From the first world war, through the roaring 20s and the Great Depression, citizens established industries and institutions that became staples of the community. With improvements in transportation and communication technology, the Wooster community became even more closely connected with the rest of the rapidly changing world.

Industry and Commerce

Wooster was the commercial epicenter of Wayne County during the early 20th century, a beacon of industry in a mostly agricultural region. Businesses such as Coxon Belleek China Company and Freedlander’s Department Store sold their wares near and far, attracting visitors and new industries.

The Coxon Belleek Company boasted some of the “the finest China on the planet,” and its wares are still highly sought after by collectors today (“Coxon Plant Visitors See Making of Finest Dinnerware in World”). Meanwhile, Freedlander’s became an iconic town destination, which expanded from a one price store in 1884 to a vast complex (“Freedlander’s.” Wayne County (OH) Wiki).

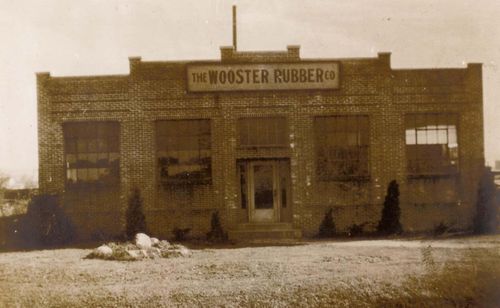

Large-scale production also increased in Wooster during the early 20th century, with new corporations flocking to the town. The Wooster Rubber Company opened in 1920, Toy Kraft began nationally selling its hand-painted wooden toys in 1916, and the Buckeye Aluminum Company, which produced lines of cookware and storage, was founded in 1902. (Wayne county wiki).

Many other businesses flourished during the 1910s and 20s. However, this great expansion of industry and production was halted by the economic crash of 1929 and the ensuing Great Depression. Many businesses struggled to stay afloat amid financial hardship and widespread loss, but some managed to survive and continue to serve the community over the following decades.

Freedlander’s Department Store

Click to learn more about the legacy of one of Wooster’s iconic businesses.

Entertainment

Downtown Wooster in the early 20th century was a vibrant center for arts and entertainment, where the community gathered to socialize and enjoy themselves. Nightclubs such as Carters and the Rhythm Room were popular throughout the jazz age. Carters served the Black community, playing music and entertaining crowds on Friday and Saturday nights, even hosting celebrities like Ella Fitzgerald and Cab Calloway. The Rhythm Room, though segregated like many venues of the time, catered to teenagers, opening its doors to white students on Wednesdays and Black students on Mondays.1Ann Gasbarre, “Bits and Pieces African-American Presence in Wooster,” The Daily Record, October 5, 2007.

In addition to nightclubs, Wooster was home to two opera houses. The Quinby Opera House put on performances, such as Shakespeare’s “As You Like It” and “Romeo and Juliete,”2“Quinby Opera House, The.” Wayne County (OH) Wiki. Meanwhile, the Wooster City Opera House held musical performances, comedy shows, and occasional religious services.3“Wooster Opera Houses Illustrations” Accessed June 17, 2021. https://ohiomemory.org/digital/collection/p16007coll34/id/76/.

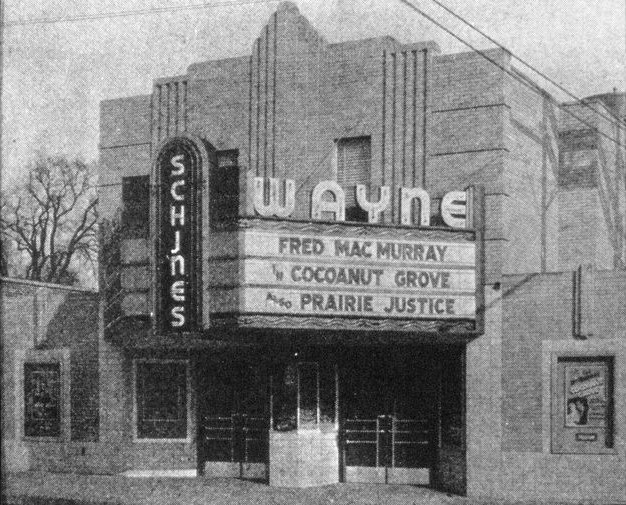

The Lyric Theater, renamed Schine’s Wooster Theatre in 1931, was also a prominent social hub. It showcased movies from the earliest years of cinema, through Hollywood’s golden age, and into the latter half of the 20th century.4“Lyric Theatre.” Wayne County (OH) Wiki, n.d. https://wiki.wcpl.info/w/Lyric_Theatre.

Education

The University of Wooster, which would re-establish itself as the College of Wooster in 1914-15 continued to offer opportunities to students in accordance with the ideas laid out in the Inaugural Letter of the University. During this time, women’s literary societies like the Willard and the Castalian gave women a voice, as they wrote about and discussed issues such as women’s suffrage.5Notestein, 46. Unfortunately, the University was left without a home when its Old Main building was destroyed by a fire in 1901.6Notestein, 229. The tragedy launched the school into a new period of expansion, with the construction of buildings, such as a new dormitory in the summer of 1910.

The College of Wooster was far from the town’s only academic site in the early 20th century; the Ohio Agricultural Experiment Station continued to enrich the agricultural practices and knowledge base of farmers in the state. At the turn of the century, it shifted its focus to addressing the diminishing labor force in agriculture due to emerging technologies that expedited farming.7Ohio State University, “A BRIEF HISTORY OF OARDC,” History, accessed February 27th, 2022. oardc.osu.edu/about/history.

Likewise, at this time, public schools in Wooster also begin to blossom. The start of the twentieth century saw the establishment of athletic and music programs at Wooster High School.8Dan Cottle, On the Corner of Bowman and Quinby: The First 126 Years of Wooster High School (Wooster, Ohio: Murr’s Printing, 1993), 16 and 42. Additionally, other clubs expanded, including “literary organizations” and a speech and debate club, which led to public orations and essays from students9Cottle, 38-39. As the school grew, it became increasingly difficult to house these new clubs.10Cottle, 7. In 1925, under the direction of superintendent George Maurer, a new Wooster High School building was constructed, which would be used until 1994.11Cottle, 67.

Immigration and New Communities

Wooster saw an influx of Italian immigrants around the turn of the 20th century, as the flourishing U.S industrial economy drew them from across the ocean. Upon arrival they were assisted in buying homes, earning citizenship, and securing jobs from Italian American citizens in Wooster.12Ann Gasbarre, “Wooster’s Italian-American Heritage Began with Raphael Massoni,” The Daily Record, August 3, 2018. One prominent figure was Joseph Digiacomo, a merchant immigrant, who oversaw the construction of a hall for Italian arrivals, which functioned as a gathering place where foreigners could learn English.13linor Taylor. “56-Year-Old ‘High-Rise’ Built by Joe DiGiacomo,” The Daily Record, August 4, 1978.

Gathering and solidifying a sense of community was especially important since Wooster’s Italian population was heavily persecuted, as nativism fueled animosity toward immigrants across the country.14Dominic Iannarelli, “Little Italy, A Touch of Italy in Wooster,” The Daily Record, 1968. A Dalton Gazette article from 1905 calls the United States a “dumping ground” for immigrants from Europe, specifically those from Italy and the Baltic states.15“The Scum of Europe Coming to America,” Dalton Gazette, June 15th, 1905. For new arrivals, facing this hostility, being part of a unified group relieved the burden of homesickness and isolation.

Aside from new communities created out of immigration, the turn of the century saw both cultural and economic contributions from the Black community, even in the face of discrimination and segregation. For example, Lucy Follis, the aunt of professional football player Charles Follis, was the piano player at the Lyric Theatre.16“Bits and pieces: African American presence in Wooster.” Traditions became a part of the Black community at Wooster, including yearly banquets and end-of-the-school-year celebrations. However, discriminatory policies confined many Black families to the east and south sides of Wooster, where many continue to live today.17Paul Locher, “Blacks coming to Wooster in early 20th century sought employment,” The Daily Record, October 9th, 2008.

Wooster and World War I

Like the rest of the United States, Wooster was heavily impacted by World War I in 1917. During this time, men from Wayne County left to train and later serve in Northeastern France. Soldiers from Wooster were a part of the Meuse-Argonne offensive, the largest offensive that included Americans.18Edward Harry Hausenstein, A history of Wayne County in the World War and in the wars of the past (Wooster, Ohio: Wayne County History Co., 1919), 105-111.

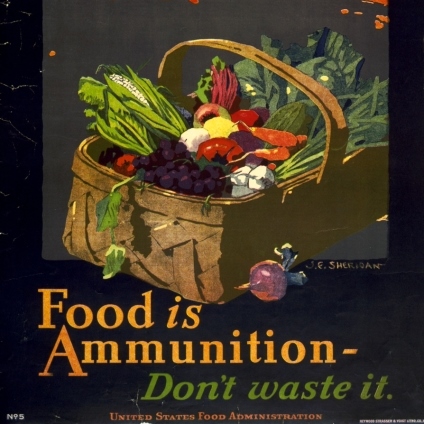

Those who stayed behind in town also contributed to the war effort through fundraising campaigns. For instance, community members purchased liberty loans, a nationwide war bond. In Wayne County, some of these campaigns raised over a million dollars (in World War I era money) for the war effort.19Hausenstein, 244, 252-256. Other fundraising projects included the program for War Savings Stamps and food conservation efforts from the Women’s Council for National Defense. Likewise, other local organizations such as the Knights of Columbus aided in the raising of funds.20Hausenstein, 277-278.

However, aid to the Allied cause was not just monetary. Many corporations in Wayne County contributed their factory production to the war effort. The Woodard Machine Company assisted in building ship parts for “torpedo craft,” and the Buckeye Machine Company built canteens for not just American soldiers, but all of the Allied forces.21Hausenstein, 272.

The College of Wooster had to change gears during World War I. Many students left for the service, while others volunteered to do farm work. Military training was required for all men on campus, which resulted in the creation of the Student Army Training Corps (S.A.T.C) at the college. Some campus buildings were turned into barracks or officer’s quarters, such as Kenarden Lodge (which would also become a hospital during the 1918 influenza epidemic) and Taylor Hall.22Wooster Quarterly 1917-1918, The College of Wooster.

The war ended on November 11th, 1918 and Wayne County met the news with great enthusiasm.23Hausenstein, 119-121.

Social Movements

Across the United States in the early 20th century, social movements both new and old were gaining momentum. Wooster was no exception; the town’s residents were active in a range of movements that connected them to wider national communities.

Wooster was active in the movement for women’s voting rights. Articles from the Wooster Daily News in 1912 and 1913 speak of the Equal Suffrage Club, which was run by a group of Wooster women.24“Suffrage Meeting Held Saturday.” Wooster Daily News, March 17, 1913, 4. https://www.ohiomemory.org/digital/collection/p16007coll38/id/4726/rec/1. The group met frequently with the goal of preparing its members for when they would be allowed to vote (“Suffragettes More Active”). They also read and discussed papers on the topic of women’s suffrage and promoted the cause to the wider community.25“Suffragettes More Active.” Wooster Daily News, March 21, 1913, 1. https://www.ohiomemory.org/digital/collection/p16007coll38/id/4751/rec/1. In a local parade, for example, the group decorated a car with flowers, dressed in white, and carried a banner proclaiming the “votes for women” slogan popular around the country26“The Parade.” Wooster Daily News, August 4, 1913, 2. https://www.ohiomemory.org/digital/collection/p16007coll38/id/5412/rec/1. Wooster’s women’s suffrage movement was in no way isolated. In 1912, the town hosted a suffragist from New York who gave a talk about the benefits of voting rights for women.27“Woman Tells Why She Wants to Vote.” Wooster Daily News, August 8, 1912, 1-2. https://www.ohiomemory.org/digital/collection/p16007coll38/id/14872/rec/1. Though the movement died down with the passage of the 19th amendment in 1920, Wooster’s involvement exemplified its connection to the wider world and the ambition of its citizens.

Not all social movements had such positive goals, however. For example, the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) targeted people of color, non-protestants, and immigrants—especially in the early 20th century.28“Ku Klux Klan.” Ohio History Connection). They burned crosses, organized parades, and held marches meant to rally support and antagonize outsiders. One reason for the growth of the KKK in Wooster may have been the popularity of the 1915 propaganda film The Birth of a Nation, which romanticized the origin of the Klan and was repeatedly shown in the Lyric Theatre.29“The Birth of a Nation,” Creston Journal, March 20th, 1918. However, many residents resented Klan activity, such as the Knights of Columbus, who famously refused to march with them in the 1924 Memorial Day parade.30“Klan’s Injection Into Parade Causes K. of C. to Leave Line of March,” Arnold Lewis, Wooster in 1876. As the 1920s progressed, the Klan became infamous for their acts of terror and less for their “Christian ideals” and “small town values,” causing their membership to decline.

Another social movement that declined in the early 20th century was the Women’s Christian Temprance Movement, which sought to end the sale and consumption of alcohol, believing that liquor was corrupting the community. Before prohibition, women in Wooster paraded through town reciting prayers and hymns, encouraging saloon owners to close their businesses. In 1874, Francis Willard (who would later become president of the movement) even spoke at a meeting in Wooster Ohio. Additionally, in 1877 the Quinby Opera House hosted a production of “Ten Nights in a Bar Room,” a successful drama that encouraged support for temperance. The efforts of the movement led to the 1908 ban on alcohol in Wayne County, and eventually its criminalization across the United States with the 18th amendment. However, in Wooster the restrictions were never enforced, and the town’s 16 saloons continued to function—save for one owned by a man who was so moved at a temperance meeting that he willingly closed his tavern31Notestein 128, Lewis 107-108 Nationally, crime surged as people continued to drink and the country gradually grew frustrated and gave up on prohibition, legalizing alcohol again in 1933.

Conclusion

During the first turbulent decades of the 20th century, the city of Wooster continued to expand. Immigrants settled in the city, creating tight-knit communities. New businesses blossomed and provided both jobs and entertainment for the population. Opportunities for education and learning also grew as time went on. Despite the hardships of war, disease, financial crises, and discrimination, the people of Wooster stayed resilient and ready for the years to come.

For further reading:

1) Hausenstein, Edward Harry. A history of Wayne County in the World War and in the wars of the past. Wooster, Ohio: Wayne County History Co., 1919.

2) Notestein, Lucy Lillian. Wooster of the Middle West. Kent: Kent State University Press, 1971.

3) Wooster in 1876, ed. Arnold Lewis. Wooster: Wooster Art Center Museum, 1976.