Long Term Diseases

Case File: Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis is one of the oldest diseases known to mankind, dating back to over 17,000 years ago. Because of this, it has maintained a visible presence in the world, particularly in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century. Consumption is the alternative name used for symptoms of tuberculosis prior to advanced enough testing. Symptoms include a bloody cough, fever, and weight loss, lasting for several years. 1 Murray, John F., Dean E. Schraufnagel, and Philip C. Hopewell. “Treatment of Tuberculosis. A Historical Perspective.” Annals of the American Thoracic Society, October 14, 2015. https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/full/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201509-632PS. Within Wayne County there has been a steady record of cases of consumption for almost two centuries. Tuberculosis would grow to have a fairly visible presence in Wooster and Wayne County, with its symptoms, supposed cures, and methods of deterring the illness becoming a focus of newspaper articles and advertisements. To this day, the influence that tuberculosis has on daily life cannot be overlooked, still claiming several hundred lives a year and infecting over a billion. 2 ibid.

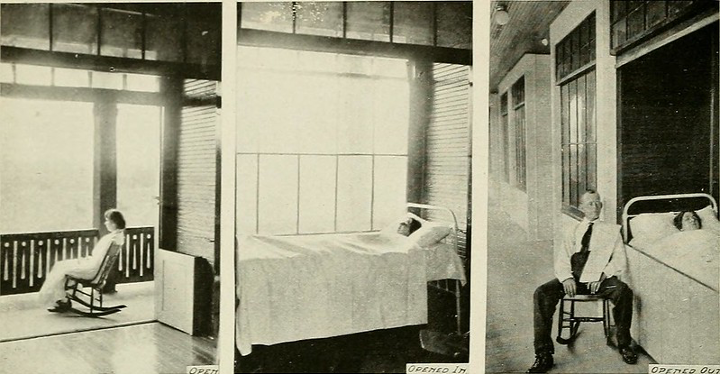

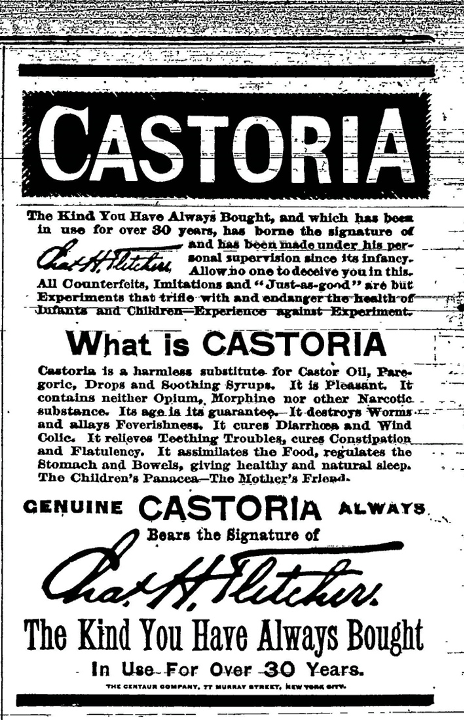

In the early 1900s, Castor oil and similar “cures” for tuberculosis were often advertised in newspapers. Such cures for illness were often deceptive as there was little governmental regulation of medicine. Another recommended way for combating the symptoms of consumption was to travel either west to the mountains or to travel to the seaside. 3 ibid This was based in previous cases where the symptoms of the disease would lessen in these settings, which eventually where looked at as being open air cures. It was often the case that the family would outright move.

After the development of the BCG vaccine for tuberculosis in the late 1920s, the death rate for the disease dropped by almost 90%. In Wayne County, there was a steady drop in mentions of the disease as the vaccine became more widely used, as discussed in several Wooster and Wayne County newspapers featured here. In today’s world, the death rate has dropped even further, with a wide range of treatments available. These treatments include use of antibiotics, the establishment of public health codes, and the standardization of vaccine usage.

Case File: Polio

For the first half of the twentieth century, a microscopic boogeyman plagued hundreds of thousands of innocent families whether they were rich or poor. This haunting aspect of life was known as the Poliovirus. Although the disease is now contained through vaccinations and treatments, for families back then it was such a terrifying presence that summers became known as polio season. Notable summers of fear occurred in the first epidemic level outbreak of the disease in 1916 and later in 1952.

Why was there such panic? The simple answer is that polio was a devastating illness that especially targeted children. Polio usually led to some form of paralysis. It might result in paralysis in one leg or two; or if the paralysis reached the spine and the torso, it could force a victim into a medical device called an iron lung just to keep them alive.

The College of Wooster and the people of Wayne County were aware of the threat and fear created by polio. In the summer of 1952, there was a bad outbreak of polio in both Wayne and Medina Counties. 4 Earl Kleinschmidt, Mabel Abbot and Ilah Kauffman. “The Health Department and Poliomyelitis: Administrative Factors in Wayne and Medina Counties, Ohio” (NCBI) 1109-1114. The fear of this outbreak led to schools reopening two weeks later than normal and led to both counties cancelling their annual county fairs. In the College, almost every copy of The Wooster Voice for the fall semester featured a brief notification that a student would not be able to return as they had contracted the virus over the summer.

Polio and the Disability Rights Movement

There are few diseases as intertwined with disability as Polio. In many ways, Polio was instrumental in the development and success of the disability rights movement because it caused a sharp increase in the percentage of the population living with life-altering disabilities. Therefore, in the second half of the twentieth century, the rights of people living with disabilities became a more visible issue. 5Crip Camp: A Disability Revolution. Directed by Newman, Nichole and Lebrecht, James. London: Netflix, 2020

People living with the effects of polio formed an essential cohort within the movement. The disability rights movement was, and is, a social movement which continues to address the fact that the problem with disability is not with the body of the disabled, but in the way in which able-bodied people respond. 6 ibid

Northeastern Ohio played an important role in polio-based disability activism. In 1907, Edgar Allen, a businessman from Cleveland whose son died in an accident due to a lack of hospital beds, built a hospital in Elyria Ohio. The hospital had a ward where children with polio could receive treatment and attend classes. While running the hospital, Allen was exposed to disabled children who were often hidden from view. Inspired, Allen founded the National Society for Crippled Children- the country’s first disability services non-profit organization, which was later renamed Easterseals. 7 “The Story of Easterseals,” Easterseals. Accessed June 29th 2020. [ /mfn] Easterseals is best known for it’s fundraising campaign for polio in which people could purchase “seals” for one dollar. Early advertising for the organization featured children with polio and slogans such as, “Hey Mister! Lend Me a Dollar to Help Me Walk!” 7 Easterseals. “Hey Mister.” Life Magazine. April 2, 1965.

Easter Seals, 1939-1941

Case File: HIV/AIDS

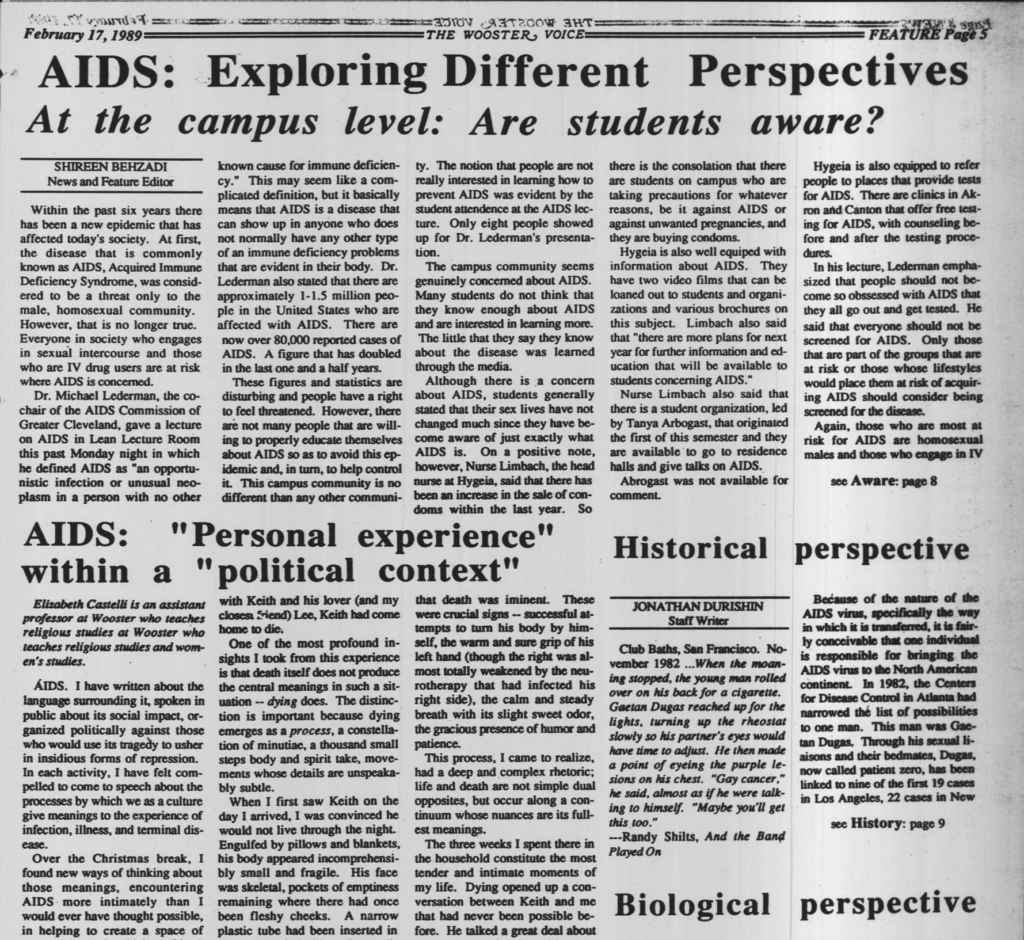

On February 17th, 1989, The Wooster Voice dedicated a feature page to AIDS. At a glance, it seemed that the campus was hosting an active discussion about the deadly virus which several years prior had been identified as HTLV-III/HIV: a retrovirus transmitted through sexual contact, blood, and needles. However, bold letters across the top of the page proved contrary, “ARE STUDENTS AWARE?” The answer was no. When commenting on a lecture given to the campus by the chair of the AIDS Commission of Greater Cleveland, the author noted,

“The notion that people are not really interested in learning how to prevent AIDS was evident by the student attendance…only eight people showed up.” 9 Behzadi, Shireen. “At the Campus Level: Are Student’s Aware?” The Wooster Voice. February 17, 1989. 5.

The general lack of interest in AIDS among students at Wooster followed a broader trend of a silence surrounding the disease. The virus was considered shameful, and despite contrary scientific evidence, was still associated with gay sex. This can be seen in another article on the same page which, following national discourse, placed the blame for the epidemic on patient zero. The article focused heavily on the patient in question’s gayness and subsequent promiscuity claiming that, “he travelled extensively and picked up men wherever he went.”

The article suggested that the man in question continued to have unprotected sex after his doctors told him not to, and concluded that he was responsible for, “countless direct and indirect victims.” 10 Durishin, Jonathan. “Historical Perspective.” The Wooster Voice. February 17, 1989. 5.

That is not to say that campus attitudes towards the virus in the late eighties were universal. By covering campus failure to respond to the AIDS crisis, the articles in question, adopted an activist tone. In the same edition of the Voice, Professor Elizabeth Castelli recounted her experience helping her AIDS positive best friend die with dignity. The professor wrote,

“By communicating this personal story, I hope to raise also the political questions concerning the death of my friend. If we as a culture take seriously the heightened consciousness of suffering… [how might that] challenge the silence/death that dominant cultural meanings surrounding AIDS impose?” 11 Castelli, Elizabeth. “AIDS: A ‘Personal’ Experience Within a ‘Political’ Context.” The Wooster Voice. February 17, 1989. 5. In other words, through her experience, the professor was advocating for an end to the silence and repression the AIDS crisis generated. In totality, despite a general apathy towards AIDS education, the College of Wooster was host to a variety of diverse conversations about AIDS in the years to come. The impact of the HIV/AIDS crisis on the College of Wooster campus would grow to become an opportunity for the campus to improve itself, particularly in the areas relating to those who were HIV positive. This would continue to grow throughout the 1990s. The AIDS crisis had long been used to discriminate against the LGBTQ+ community. However in the 90s, the crisis would foster a new conversation of LGBT+ rights leading to increased inclusion on campus. 11 Peter T. Stratton, “Reflections,” The Wooster Voice (Ohio), October 19th, 1990

Impact of the HIV/AIDS Crisis

“Through education and activism, we have fought against the ignorance and prejudice that so often characterized the response to the epidemic.”

Sohil N. Parekh, ”AIDS Quilt Comes to Wooster,” The Wooster Voice, April 19, 1996.

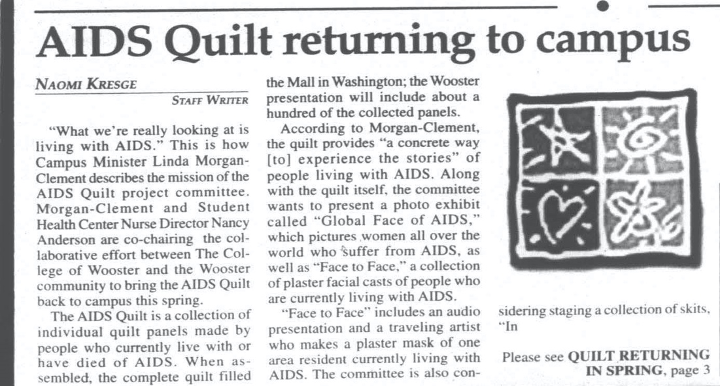

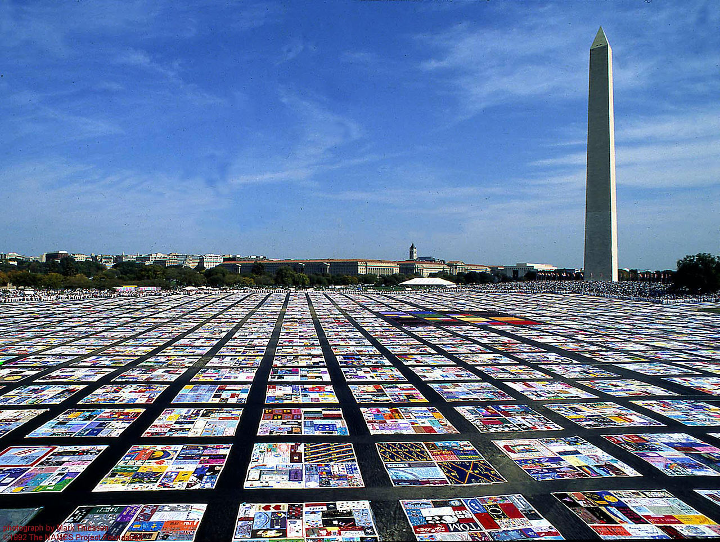

The AIDS crisis would eventually see the entrance of another important part in this period of campus history: the Names Project Aids Memorial Quilt. This quilt, which has been brought to Wooster a total of 5 times, is a visual representation of all the lives that were lost to the virus. The campus, working together with a group of volunteers from the town to form the AIDS Quilt project Committee, was able to use the quilt to bring awareness to the tragedies of the AIDS crisis and all the lives that had been lost. 12 Naomi Kresge, ”AIDS Quilt returning to campus,” The Wooster Voice (Wooster), September 9, 1999

If there had not been volunteers and members of the Wooster community so dedicated to bringing a range of personal stories and panels to the community through the quilt, it is doubtful that the quilt would have been as impactful as it was.